Earth is home to an extensive web of incredibly complex and wildly diverse ecosystems. The harmonious interaction among these ecosystems is what allows life to thrive at Earth’s deepest depths and highest peaks. But one species has upset the balance.

Earth is home to an extensive web of incredibly complex and wildly diverse ecosystems. The harmonious interaction among these ecosystems is what allows life to thrive at Earth’s deepest depths and highest peaks. But one species has upset the balance.

“It’s no secret that humans have had an impact on Earth’s biodiversity,” said Molly Corder, a spring 2018 graduate of the Department of Biology’s Professional Science Master’s (PSM) in Zoo, Aquarium and Animal Shelter Management. “Today’s scientists are tasked with the race against time to save endangered species and bring back nearly extinct ones,” she said.

Finding her calling

Corder credits the Colorado State University PSM program for opening the door for her to join the ranks of a generation of scientists determined to undo the biodiversity loss that has become so evident in today’s world. Here, she found a new passion in conservation medicine, the study of the overlapping features among human, animal and environmental health. This discovery was inspired by the wide variety of classes she took, which ranged from animal behavior, biomedical and reproductive sciences to nonprofit conservation administration, marketing and applied data analysis for clinical research.

“I love the PSM program because in many ways this master’s degree is like a blank canvas,” said Corder. “You find what your passion is here, and then you’re given a paint brush to bring your own creative approach to conservation. We’re not asked about what we want to be when we grow up. We’re asked about which problems we want to solve in the world. Before coming to CSU, I had never heard about conservation medicine. Now I plan to make it my career.”

The PSM degree offers a unique opportunity for students to blend business skills and applied science with a specific focus on helping animal organizations. This dynamic and flexible program provides students who have a passion for animals with the tools necessary to make a difference by allowing them to build their own degree that is suited to their specific career goals.

“PSM students dedicate their careers to improving animal welfare and conservation science with the hope that zoos will be able to work together to restore critically important habitats and provide a better world for animals,” said Corder.

Zoos: a modern-day ark

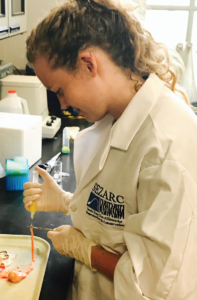

During her time as a PSM student, Corder also studied and conducted research at the South-East Zoo Alliance for Reproduction and Conservation in Yulee, Florida. The not-for-profit group connects scientists, veterinarians and animal managers with forward-thinking zoos, aquariums and wildlife preserves to provide solutions to reproduction challenges. There, Corder was able to apply reproductive techniques that she learned at CSU, such as gamete rescue (the recovery of reproductive cells from recently deceased animals) and cryopreservation (the ability to freeze and thaw these cells while keeping them viable) with exotic animals in the field.

During her time as a PSM student, Corder also studied and conducted research at the South-East Zoo Alliance for Reproduction and Conservation in Yulee, Florida. The not-for-profit group connects scientists, veterinarians and animal managers with forward-thinking zoos, aquariums and wildlife preserves to provide solutions to reproduction challenges. There, Corder was able to apply reproductive techniques that she learned at CSU, such as gamete rescue (the recovery of reproductive cells from recently deceased animals) and cryopreservation (the ability to freeze and thaw these cells while keeping them viable) with exotic animals in the field.

“We worked on everything from staghorn coral to African elephant reproduction,” said Corder. “It was an experience I will never forget.”

Corder’s CSU capstone project focused on examining the value of zoos in clinical research and conservation medicine, with an emphasis in reproduction for an endangered miniature buffalo species, the lowland anoa. Her research helped improve the timing and accuracy behind their reproductive procedures.

Corder also helped with fertility exams on cheetahs and elephants as well as working to pioneer the gamete preservation technologies on sharks and stingrays to improve and increase captive breeding in aquariums. She assisted with a field project that successfully preserved gametes from a recently deceased Banteng, an endangered bovid species in Indonesia.

“Zoos are so much more than entertainment parks,” said Corder. “In many ways, zoos are ‘arks’ for the future of our planet’s biodiversity. It’s hard to comprehend, but the wild doesn’t really exist anymore, at least not like it used to. Humans have reached even the farthest corners of the world. This has created competition for resources and brought about new challenges in maintaining ecological health. And of course, there are geopolitical and social issues that are deeply intertwined with ecological integrity.”

Hope for endangered species

The world held witness to the death of the last male northern white rhinoceros last March, after the species endured decades of poaching and habitat loss. Corder worked with the South-East Zoo Alliance for Reproduction and Conservation to generate data to inform the San Diego Zoo’s Northern White Rhino Initiative; this program attempts to resurrect the now functionally extinct species with cutting-edge technology. She performed some of the hormone testing involved in predicting and manipulating the ovulation events of southern white rhinos, a closely related sub-species. Just this summer, the Northern White Rhino Initiative announced that one of the female southern white rhinos transported from Africa is pregnant from an artificial insemination procedure.

“This is one of the first times this has happened, which is a huge win for the conservation science community,” said Corder. “It means that while it’s still a long shot for [northern white rhinos] to be saved from extinction, it may be possible. Even if we’re not successful at saving this sub-species, this research will lay the foundation for assisted reproductive technology development used to help other critically endangered species.”

CSU researchers have used reproductive technology such as in vitro fertilization to bolster bison populations that are also free of brucellosis, a population-threatening disease.

A bright future

Corder has accepted a position to become a Smithsonian scientist, where she plans to keep working to end extinction. She will also be pursuing her doctorate with George Mason University in Washington, D.C., and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. She hopes to build on the existing research that modifies assisted reproductive technologies for endangered species in addition to adding a further level of clinical research and conservation medicine.

“Endangered species are why I wake up in the morning,” said Corder. “It’s time for conservationists to move past whistle-blowing and finger-pointing. We’ve got to be the change we want to see in the world. Solutions are possible, and we have the power to make a difference.”