Whether smuggled in by container ship to New York, or by passenger plane to LAX, a dead endangered or exotic animal without paperwork will often end up confiscated by the U.S. government – and then shipped to a vast storage warehouse in Colorado.

Now, however, such an item could forge a new life in education, in Colorado State University’s Department of Biology. Thanks to the hard work of one undergraduate, the University recently acquired 105 such specimens for its teaching collections.

“We got a bit of everything under the sun – from snail shells to antelope taxidermy,” said third-year zoology-turned-fish, wildlife and conservation biology major Austin Colter, who spearheaded the acquisition efforts. “And they want to give us a lot more.”

Next-to-last stop

On the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge’s windswept grasslands outside Denver sit a hodgepodge of government agency outposts – from U.S. Army facilities to black-footed ferret rescue operations. One nondescript building is the massive U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wildlife Property Repository.

Inside are endless rows of shelves and crates, housing millions of confiscated animal products brought to the U.S. illegally – from skins to taxidermy to household objects fashioned from horn and bone.

Last December, Colter, who is also minoring in conservation biology, entomology and zoology, found himself on a tour through these macabre aisles while attending a conservation career symposium at the Wildlife Refuge. He learned that because the objects are contraband, the government is unable to sell them. Instead, it can only donate the pieces on permanent loan to institutions for educational purposes. “That’s the only way they can get rid of these items,” Colter said. And with more objects coming in constantly, the agency is keen to find opportunities to deaccession.

Fortunately for the National Wildlife Service – and for CSU – Colter is an aspiring museum collections curator. He has spent countless hours volunteering time on skeleton reconstructions in the lab of Associate Professor Shane Kanatous and completing specimen repair for other faculty in the department. And he knew an opportunity when he saw one.

“It just clicked,” Colter said. “So I just started asking questions then and there” about whether they would consider donating specimens to CSU. “And that’s when the process started.”

Two weeks later, he and Kanatous’ lab were back in the warehouse, walking past strangely posed exotic cats, mounds of dried sea horses and mounted rhinoceros heads. This is no American Museum of Natural History storeroom. Like items are grouped together for storage purposes, rather than curatorial or research ones. “It’s just piles and piles of the same python skin, and over there are all the antelope – it’s asinine and disgusting and also breathtaking in some sense,” Colter said. From this trip, the CSU group created a wish list of sorts, turning it over to the Wildlife Service to see what they could do.

A new home

On a sunny day in early February, Colter and the Kanatous lab had their hands full. They had just returned from the repository with a truck full of confiscated animal specimens – and now had to unload them in their new home.

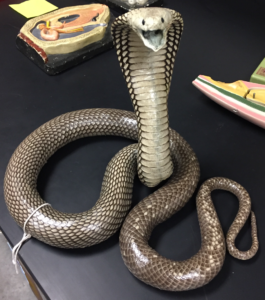

The items include a giant sperm whale tooth, a full-sized African bontebok, a pristine zebra head, a small leopard, and a disarmingly lifelike cobra posed to strike – and are enough to captivate even those outside of the sciences. All 105 rare pieces now live in the new Biology Building’s central collections space. There, all of the department’s collections can be stored together for use in teaching and research – and in controlled conditions for monitoring and maintenance.

In the Anatomy-Zoology Building, where the department spent the past few decades, much of the department’s collections had been scattered through display cases, labs and offices. Colter worked with many faculty during the department’s recent move. He said they would occasionally discover forgotten specimens – you would look into a back corner, and “it would just be a cabinet of raccoons,” he said. “In the new building, everything that was once scattered is now in one room.”

The department’s historical collection emphasized regional species. “But here we are teaching students about tropical ungulates and wild, colorful birds,” Colter said. “So it seemed like the perfect opportunity to at least get ahold of some of that diversity.” Kanatous agrees. The new acquisitions “will introduce students to many different sorts of organisms,” he said.

Items from the National Wildlife Service technically remain federal government property and must be tracked carefully. But faculty teaching relevant courses are encouraged to borrow the new items for instruction. For his part, Kanatous is grateful for the generous donation, acknowledging that he is also disappointed that there is still so much illegal trafficking to make such a gift possible.

He is also appreciative of Colter’s bright idea and hard work. “Austin was integral,” Kanatous said. “Without him going there, finding this repository and coming back and speaking out about it, we would not have gotten this,” he said, gesturing to the new animals.

Recently, Colter was working in the collections space when a staff member brought her young children to see the new specimens. Witnessing the kids’ unbridled excitement at seeing these rare animals in person made Colter a little misty-eyed. “Because that’s why I did this,” he said, “for education.”